1. Aren’t most rental properties already in good condition?

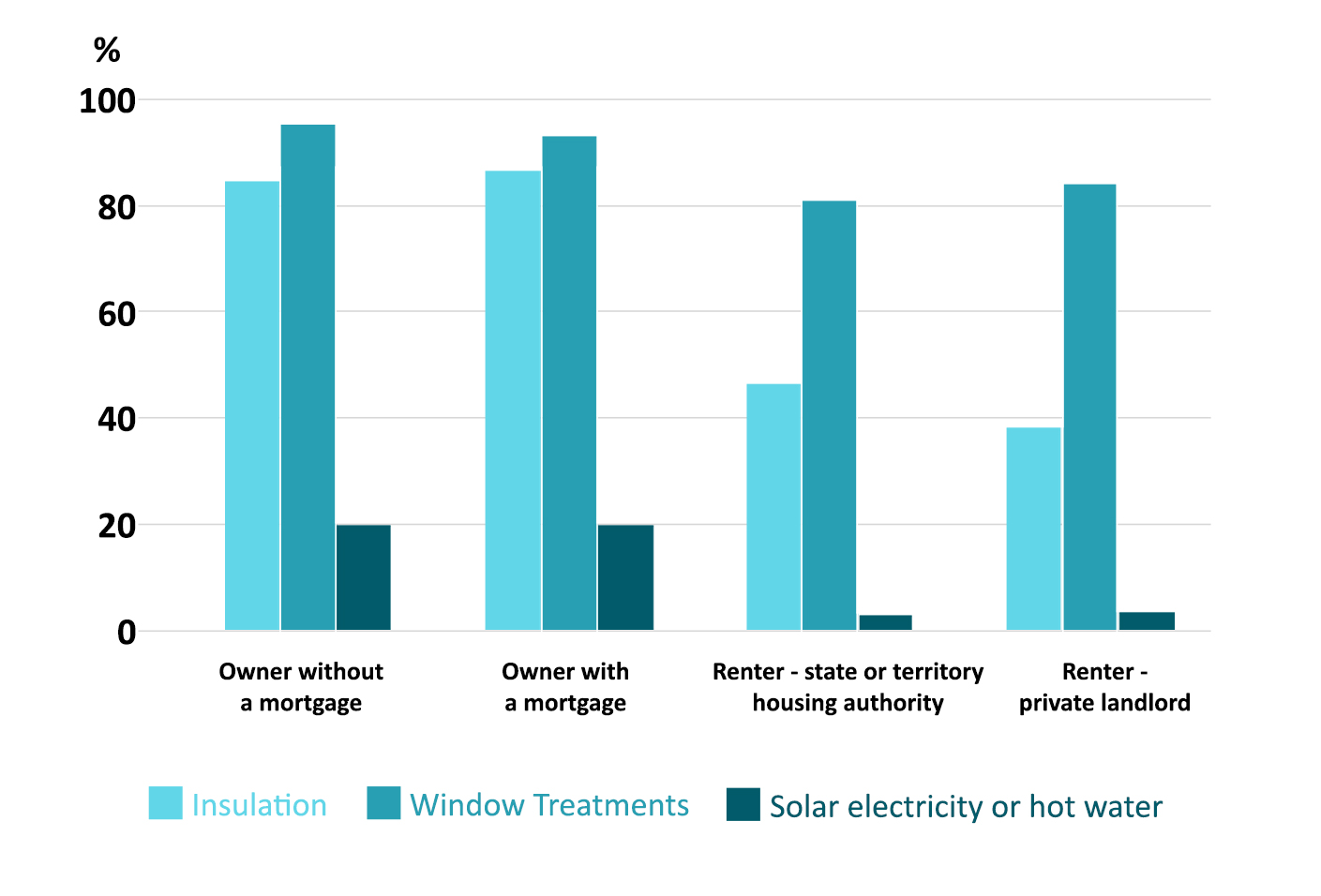

The overall poor efficiency of Victoria’s housing stock means that many homes that are in otherwise good condition are nevertheless likely to be inefficient. On average, rental properties are worse in terms of efficiency, with much lower rates of basic measures such as insulation in rented versus owner-occupied homes.

Current laws governing repair and maintenance only require landlords to return a property to the condition in which it was leased. If a property did not have insulation or a fixed heater, there is no obligation under current legislation to provide it.

2. Aren’t rental properties already required to meet building standards?

Buildings in Victoria are subject only to the standards that applied at time of construction.

A rental home which met building standards in place when it was constructed is not required to meet any upgraded standards which have been introduced since then. [1] As standards for new buildings, particularly for efficiency performance, have been progressively raised since 1990, the lack of matching standards for rental properties is creating a two-tier housing sector.

3. Do voluntary incentives work?

Unfortunately, voluntary market incentives often don’t encourage landlords to invest in efficiency upgrades because the benefits of lower bills and better living conditions mainly accrue to tenants. This is known as the ‘split incentive’ problem, because the benefits of lower bills and better living conditions mainly accrue to tenants.

We know from experience that most landlords don’t take advantage of voluntary efficiency programs, even when they are subsidised. On the other hand, tenants are often reluctant to request efficiency upgrades for fear of eviction or rent increases, especially if they are disadvantaged.

4. Isn’t renting normally temporary?

Not any more. As house prices have risen, home ownership has become unaffordable for an increasing number of Victorians, and renting is becoming a long-term situation. The latest Census data shows 1 in 3 households are now renters, up from around 1 in 4 in 1991, and the proportion of households renting for longer than 10 years has doubled since the 1990s.

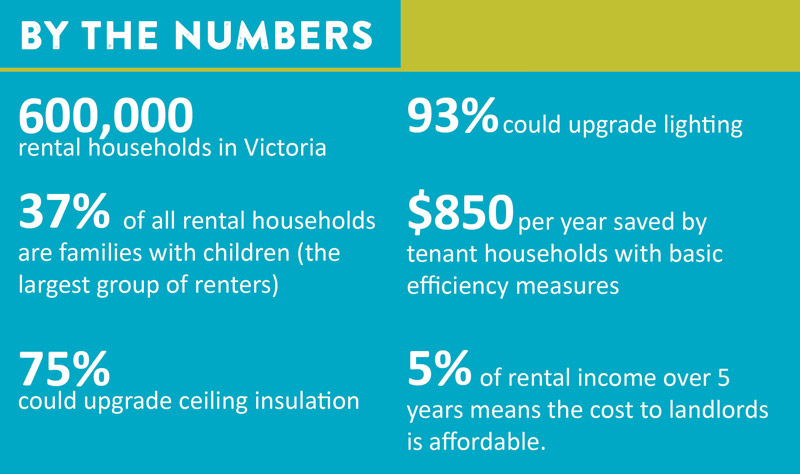

The face of rental households is also changing. Whereas once singles and young people dominated the private rental market, since 2011 families with young children have represented the largest group of renters in Victoria. [2]

5. Can’t tenants just avoid poor quality houses?

In Victoria there is no requirement that real estate agents disclose the energy star rating of a property when it is leased and many important elements, such as ceiling insulation, are not possible to inspect at an open house. We also found that, when asked, many real estate agents do not even know how well a given property is insulated. Consequently, prospective renters can find it almost impossible to make an informed choice.

Furthermore, in a highly competitive rental market such as Melbourne, many tenants have little market power to choose between properties in their price range. This long-standing situation affecting vulnerable tenants is getting worse as an increasing number of middle-income tenants, who a generation ago would have moved into home ownership, are now staying in the private rental market, pushing lower-income households into more and more marginal properties.

Because these marginal properties are not required to meet any basic standards, already vulnerable people are being exposed to additional health and cost of living pressures.

6. What about rents and evictions?

Keeping compliance costs reasonable and allowing landlords to spread investment over several years will reduce pressure on rent increases. We also recognise that additional protections will be needed in the new rental laws to guard against unreasonable rent increases.

Flagging compliance dates well in advance and allowing landlords to spread investment over several years will keep costs to around 5 percent of median rental income (see below). Costs of this magnitude do not justify rent increases above CPI. However, we recognise there’s a risk some landlords could use standards as an excuse for unreasonable rent increases, which is why we are also calling for additional protections in the legislation. We are also recommending that rental properties be required to comply at the start of a new lease. This will deliver rolling compliance across the rental housing stock as leases take effect at different times, avoiding sudden shocks to the market and minimising the risk of evictions.

There is little evidence from other jurisdictions such as the UK, Canada and New Zealand that the introduction of standards has had any significant impact on housing supply or rents. Queensland has also recently announced it will introduce rental standards in the near future. This campaign is being led by the One Million Homes Alliance of Victoria’s leading social justice and consumer organisations, who strongly believe the environmental, health and energy affordability benefits vastly outweigh the risks of adverse consequences.

7. What could the cost be for landlords?

It is not unreasonable to ask property owners to provide an essential service in a manner that does not endanger other people’s safety and well-being, in the same way that restaurant operators, transport providers and a range of other businesses face obligations relating to public safety.

Sustainability Victoria research indicates that a package of basic efficiency measures could cost around $5500. This is not an onerous obligation for property investors earning upwards of $20,000 every year in rental income or $100,000 over the 5-year implementation period. Compliance costs are likely to be lower for landlords who already keep their properties in good repair. Furthermore, most property investors are in the top two income quintiles, while more than half are in the top wealth quintile. [3]

8. What could tenants save on their bills?

A basic suite of energy and water efficiency could save a household nearly $850 a year on their energy and water bills. Recent electricity and gas price increases mean that savings for some households may now be even higher. On the other hand, households that are rationing their energy use or cutting expenditure in other areas to cover high energy bills may see lower bill savings but are likely to receive health benefits from improving the efficiency of their homes.

- Buildings are subject to retrospective requirements for smoke alarms and pool fencing, but nothing that prescribes an objective standard of quality or liveability.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics 2017, 2016 Census: Victoria, http://www.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2016/quickstat/2?opendocument; W. Stone et al., 2013, Long-term Private Rental in a Changing Australian Private Rental Sector, AHURI Final Report No. 209

- R. Wilkins, 2016, The Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia Survey: Selected Findings from Waves 1 to 14 – The 11th Annual Statistical Report of the HILDA Survey, Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research