- What is the brown coal fired power station licence review?

- What’s this got to do with climate change?

- What exactly is Environment Victoria recommending?

- How could coal power stations reduce their climate emissions to meet limits and targets

- Who is responsible for this decision?

- What do the power stations say about it?

- What could it mean for the Latrobe Valley?

- What about air pollution?

1. What is the brown coal fired power station licence review?

In 2017 the EPA began quietly reviewing the licences of Victoria’s three coal power stations. Initially their review was focused only on the opinions of the power station owners themselves; so together with Environment Justice Australia and community groups in the Latrobe Valley, Environment Victoria pushed the EPA to open up the process up to public input.

Throughout 2018 the EPA accepted submissions on how the licences should be updated to meet community expectations. Most of the submissions raised climate change and air pollution as the number one issue that needed to be addressed. This process culminated in a “Section 20B conference” (a kind of formal public consultation process set out in the Environment Protection Act) in Traralgon where participants once again raised climate pollution as a critical issue.

The EPA has no statutory deadline for completing the licence review, but has said they will announce their decision by March or April 2019.

Through the amended Climate Change Act 2017 the EPA has the power to reduce Victoria’s climate pollution towards the 2050 target of zero net emissions [1] and is also required to consider climate change as part of the licence decision.[2] Therefore, they have almost everything they need to put limits on climate pollution from coal power stations. However this is unlikely to happen without the support of the Andrews government.

[1] Climate Change Act 2017 (Vic), s101 which amended Environment Protection Act 1970 (Vic), s13(1)(ga)(ii)

[2] Climate Change Act 2017 (Vic) s17, s20

2. What’s this got to do with climate change?

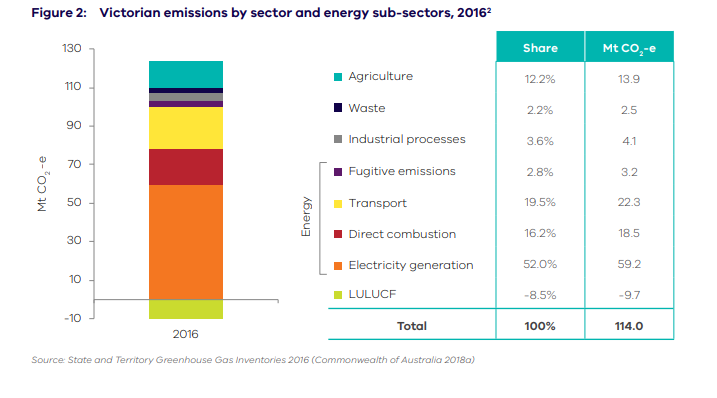

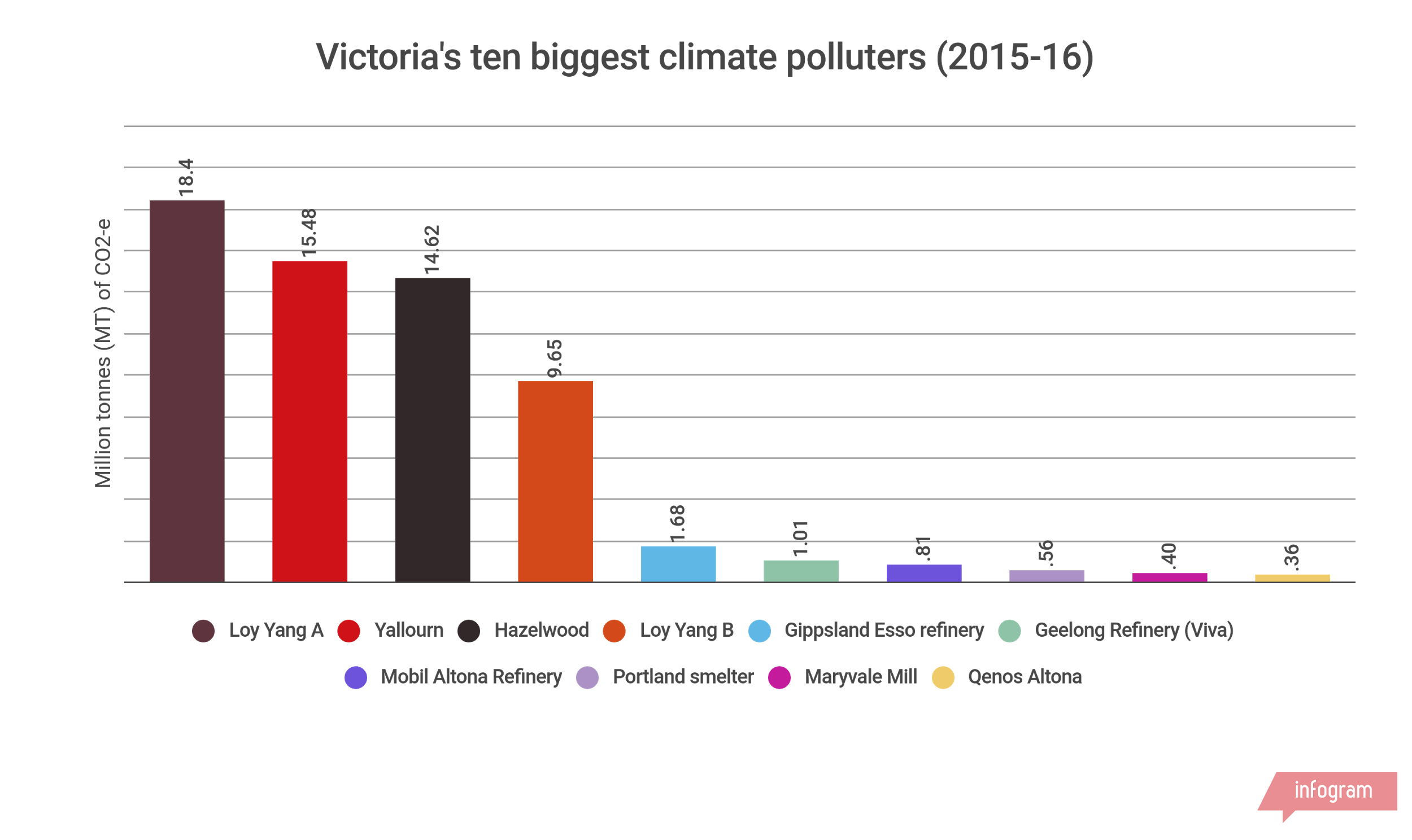

Put simply, Victoria’s three coal power stations are the state’s biggest climate polluters, responsible for around half of our state’s climate pollution (though now more like 40% since Hazelwood closed in 2017).[1] We cannot address climate change in Victoria without starting with immediate reductions in greenhouse gas emissions from coal-burning power stations.

[1] https://www.climatechange.vic.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0033/395079/Victorian-Greenhouse-Gas-Emissions-Report-2018.pdf

3. What exactly is Environment Victoria recommending?

Our key recommendation to the EPA’s licence review is that annual licence limits are placed on greenhouse gas emissions from coal-fired power stations. The EPA already does this for toxic air pollutants like sulphur dioxide, but they have ignored the greenhouse gas emissions from the same power stations.

The EPA needs to base their decision on existing government policy. So, these limits could be set to correspond with Victoria’s emission reduction targets – which is to reduce emissions by 15-20 percent on 2005 levels by the year 2020 and to reach zero net emissions by 2050.

In the absence of interim emissions reduction targets for 2025 and 2030, generators could be required to reduce emissions by three percent a year – the absolute minimum linear trajectory if we’re to hit our legislated target of net zero emissions by 2050. However, the scale and imperative of climate change warrants much faster reductions in emissions from coal.

4. How could coal power stations reduce their climate emissions to meet limits and targets

Operators of coal-fired power stations could comply with requirements to reduce their climate emissions in a number of ways:

- Improve efficiency:

- Having a limit on pollution that tightens over time sends a clear signal to operators to improve the efficiency of their facilities. While helping to cut climate pollution, this will have the added benefit of improving cost-competitiveness of their operations and reduce fuel costs.

- Curtail output:

- If power stations had an annual limit they must not exceed, operators could monitor their cumulative annual emissions and manage their output accordingly. Electricity generators already do not operate at full capacity all year round and output could be further curtailed at times of low electricity demand.

Consistent with the EPA’s new focus on harm prevention, we suggest they work closely with power station operators to determine how emissions can most effectively be reduced at each individual site. This will be most effective if there are real consequences if the power stations fail to curb their emissions. This could be the perfect opportunity for the EPA to exercise its new general duty to take reasonably practicable steps to minimise risks of harm from pollution and waste.[1]

[1] Independent Inquiry Into The Environment Protection Authority, Recommendation 12.1

5. Who is responsible for this decision?

The EPA is the ultimate decision maker in this review. However the EPA can only act within the bounds of policy and legislation set by the Victorian government.

In our view, the EPA already has the power to implement carbon pollution limits, but they still say they need more guidance from the government. This means the Premier and Minister for Environment, Energy and Climate Change need to make it clear that they expect the EPA to use its powers to regulate greenhouse gas emission. When you’re trying to stop climate change, you don’t leave a really useful tool in the shed.

We are calling on the Premier to speak with the EPA and remind them that they have the power to put limits on climate pollution as part of this review. And that they should use this power.

6. What do the power stations say about it?

During the EPA’s public consultation, the power stations said there was no need for the EPA to impose limits on greenhouse gas emissions because there was going to be a National Energy Guarantee, and that would take care of everything!

This argument has obviously not aged well. The NEG collapsed, and yet again there is no coherent climate and energy policy at the national level. And if we’ve learnt one thing about climate policy over the past decade, it’s that you should never assume there’ll be a sensible and lasting national approach to these issues.

The climate crisis is upon us now. There’s no time to waste hoping Canberra can sort out its mess. We’ve got to take every opportunity as it comes, not hold out for some magical perfect solution. Because that probably doesn’t exist.

7. What could it mean for the Latrobe Valley?

Putting limits on coal power stations could immediately reduce pollution, without putting too much pressure on the immediate viability of any of the power stations.

All the power stations operating in Victoria’s Latrobe Valley have announced closure dates between 2032 and 2050. This means that the Latrobe Valley is already preparing for a local economy that can survive and thrive without the influence of these large corporations. However, these closure dates are unrealistic in light of climate science which says all coal must be phased out by 2030, so transition planning for the Latrobe Valley needs to happen much sooner.

Since before the closure of Hazelwood power station, the Latrobe Valley community has received support from the Victorian government and wider Victorian community, who do not want to see the region suffer as a result of our state’s efforts to respond to the threat of climate change.

This support has taken the form of a $266 million transition package and the initiation of the Latrobe Valley Authority (LVA), which is coordinating economic development in the area. The LVA’s work has seen the unemployment rate decrease since Hazelwood’s closure [1] as well as a number of new businesses move to the area, such as an electric vehicle manufacturer with plans to employ over 500 people. [2]

[1] http://www.latrobevalleyexpress.com.au/story/5318577/positive-signs-one-year-after-hazelwood/

[2] https://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-10-30/electric-cars-set-to-bring-500-jobs-to-latrobe-valley/10448344

8. What about air pollution?

The coal-burning power stations are also responsible for some of the worst air pollution in the country.

The three brown coal-fired power stations in Victoria are the highest emitters of both coarse and fine particle pollution (PM10, PM2.5).[1] EnergyAustralia’s Yallourn power station is Australia’s highest emitter of PM2.5, a pollutant that is harmful to human health even at low levels.[2] Loy Yang A has the highest emissions intensity of sulphur dioxide, which contributes to itching eyes, wheezing, headaches and the onset of asthma attacks.[3] Concern has also been raised about power station emissions of nitrogen oxides and mercury.

Our friends at Environment Justice Australia have written extensively about how to reduce harmful air and water pollution from coal. You can read their submissions to the licence review here.

[1] National Pollutant Inventory Data 2015/16 < http://www.npi.gov.au/npi-data/latest-data>

[2] Neil Hime, Christine Cowie and Guy Marks, Woolcock Institute of Medical Research, Centre for Air Quality and Health Research and Evaluation (CAR), ‘Review of the health impacts of emission sources, types and levels of particulate matter air pollution in ambient air in NSW

[3] Environmental Justice Australia, Toxic and Terminal, 12.