The Guardian

Fisheries managers arrived too late to save more of the endangered species as heavy rain washes ash into NSW rivers, robbing fish of oxygenWhile the late summer rain helped put out the bushfires, it caused another environmental catastrophe – floods of ash clogging up our rivers. Here’s what happened and how we can restore our catchments to health.

Our rivers suffered this summer, and not just from the drought and fire. Summer rains also brought floods of ash.

While rivers and streams have been battered by extreme weather events before, they are more vulnerable than they have ever been.

The way we live around the rivers has changed. This summer’s bushfire crisis has revealed years of compounding harm in an instant.

Martins Creek, East Gippsland, after the 2019/20 bushfires devastated the area. The creek had wet temperate rainforest along its edge. Photo: Doug Gimesy, gimesy.com

Why are our rivers struggling?

The resilience of our rivers depends on the water flowing through them. As the climate changes, less water is available.

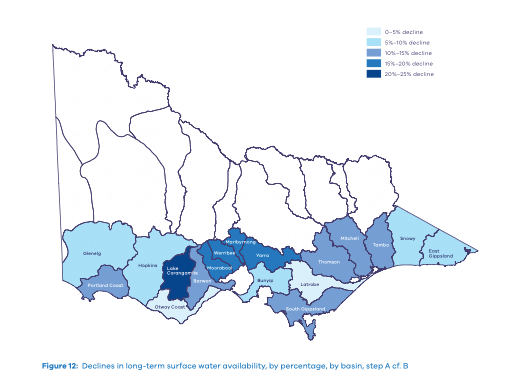

The water available in rivers, creeks and wetlands – what we call ‘surface water’ – has declined substantially over the last 20 years. Each river basin in southern Victoria shows decline, from the Otways (4%) to the Corangamite basin (21%).

Percentage declines in long-term water availability across southern Victoria – from DELWP’s Long-Term Water Resource Assessment

In the Murray region, the CSIRO projects that climate change might reduce river flows by 41% by the year 2030.

The river is shared between different uses. While water flowing into the river is declining across the board, the environment’s share of that water is often the hardest hit.

That’s because users like agriculture, industry, commerce and cities have water entitlements, a property right that allows them to access water.

But most of the environment’s share isn’t so clearly protected. Victorian taxpayers have purchased some water entitlements as well, dedicating them to river health, but they’re a small percentage of what’s required.

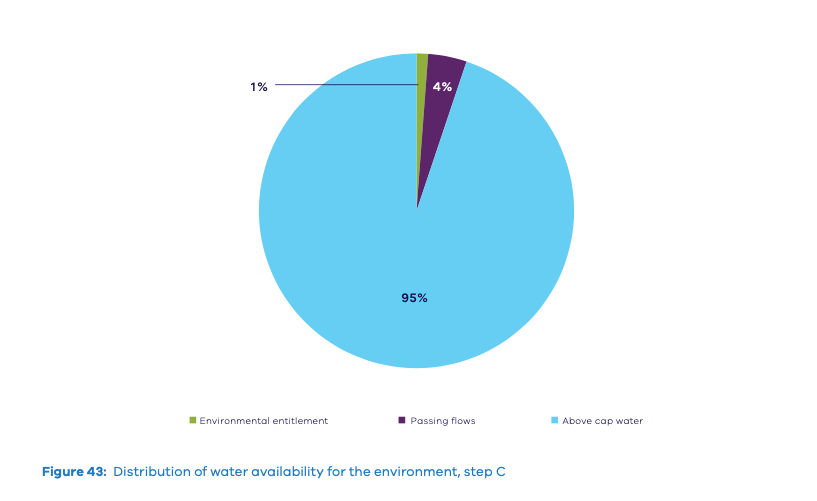

Let’s look at southern Victoria as an example. Public environmental entitlements make up just 1% of the water going to the environment. Another 4% of the water is for pushing these entitlements downstream where they are needed. But 95% of water for the environment is simply what remains after every other user has taken their share.

Above cap water makes up 95 percent of water for the environment. This is the water available after other users have taken their share. It is the most vulnerable to drying conditions

In other words, the environment gets the leftovers. When there isn’t much left, the health of the river, and river communities who depend on it, takes the hit.

Even after rule changes and recovery of water entitlements for the environment, we can’t keep up with the pace of climate impacts. The share of water for the environment has not increased in any basin in Victoria.

As a result the health of our rivers has massively declined. When too much water is taken from our rivers, they are vulnerable if a stressful event occurs – like the most recent bushfires.

How do bushfires hurt the river?

For so many communities, the late-summer rain came as a relief. But for areas hurting from drought and bushfires, the rain had a tragic side effect.

It fell on forests that had burnt, carrying bushfire ash and mud into the streams. Nutrients in the ash increase bacteria, which robs the water of oxygen. Soil smothers the stream beds and eliminates habitat. Or it can fill the river almost completely. After the rain, locals described the Macleay River in New South Wales as a “runny cake mix”.

Further inland, Mannus Creek was turned into “a river of black porridge,” with crayfish and mayfly larvae seen crawling out to escape.

The creek’s Macquarie perch, the last population in the Murray catchment, were all but wiped out.

We cannot stop the rain from falling (and we should be grateful when it does). But how do we stop the flow-on devastation caused to our streams and rivers?

What can stop the floods of ash?

Fresh flows released from dams could help dilute some of the black water. But it would be difficult to get the timing right, and it’s only possible at limited locations – for example, directly downstream of controlled dams. This is not an option for the headwaters, which is often where the forests have burned.

Local erosion control and sediment barriers might block some runoff in areas that can be reached. But these could be overwhelmed by big flows of soil and ash. Scientists need to work with local land users who understand the landscape and determine where it would be most useful. We need more data to understand where smaller flows of soil and ash are likely to happen, where they will do the most harm and where we can stop them.

This leaves us with no easy answers.

After a large fire, we know the largest floods have extreme impacts, and they are the most difficult to stop.

For smaller floods, we don’t know enough about their impacts or which ones are worth stopping.

Restoring our catchments

What we can do is two things. First, we can reduce the risk of catastrophic events by taking action on climate change.

In Victoria, we’re facing a future with more-frequent bushfires and more-severe drought. Pollution from burning coal, gas and oil increased global temperatures, drying out the landscape.

We need the whole world to cut emissions, and that starts at home. The Victorian government can set strong emission reduction targets to set us on track toward a sustainable, prosperous future.

The second thing we can do is revive our rivers so they’re better able to withstand future events.

We need to construct a new way of living in our water catchments, reconciling our lives with increasingly vulnerable landscapes and waterways.

This might involve:

- Better understanding of erosion control. This means coming together with those who have local knowledge: First Nations people, farmers, firefighters and Catchment Management Authorities. We can see where our catchments are at risk and where we can build resilience.

- Managing the land responsibly. Around the river, developers have taken over the floodplains, clearing and eroding the land. Some changes make the land more susceptible to bushfires, some more susceptible to post-fire erosion. We need to work with planners to regulate this.

- Securing the river’s right to water. Too much water has been taken from our rivers for profit, for too long. The flows have been altered to suit the interests of a few corporate irrigators. We can look at how water use is changing in our catchments and demand more protected water entitlements for the river.

Many of us are accustomed to looking at what needs to change and who needs to take less water. We have to get better at understanding who is most vulnerable in the change that needs to happen.

Which workers will need new jobs? How do we leverage a town’s economic assets to create wealth for the community? How do we use that wealth to develop opportunities for people in a future where we use less water? We know that a lot less water will be available due to a hotter and drier climate – how can we plan for that now?

The health of our rivers is inseparable from the health of our communities. They are mutually indebted.

There is not a simple solution to drought, fires and floods. But there is a simple place to begin: taking a closer look at our rivers and waterways, recognising how they are hurting and how they can be restored, and what communities can do to prepare for the future.