The Age

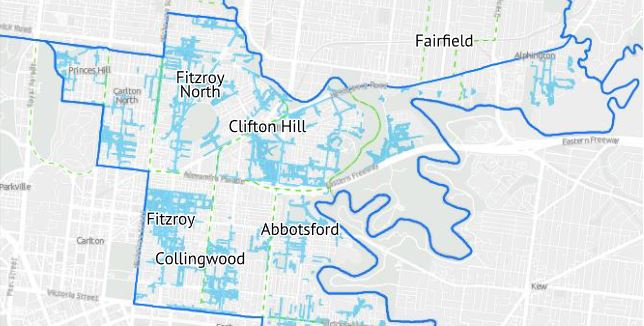

More than a third of all properties in the City of Yarra are at risk of flooding from overflowing drains, according to new modelling.In Victoria, extreme short-duration ‘rain bursts’ are becoming more intense and more frequent – especially during summer when thunderstorm rainfall is increasing. An increase of 14% has already been observed in the amount of rain that falls during these events. [1]

Our existing infrastructure was not designed to cope with with these unnatural extremes, and flash flooding is set to be a growing issue. For example, in December 2018 a month’s worth of rain fell in less than 24 hours, flooding the main street of Albury and trapping at least 100 cars on the Hume Freeway north of Wangaratta.

Images show the effects of flash flooding on the Hume Highway and in Albury's main street. Source: ABC News

More recently, updated flood modelling for the City of Yarra revealed more than a third of all homes are now at risk of flooding from overflowing drains. And with citywide mapping expected from Melbourne Water by 2026, it’s likely that far more homes will be found to be at risk.

The underlying cause

By burning coal, oil and gas, humans are pumping our atmosphere full of carbon dioxide and methane which trap heat like a blanket around the earth.

This causes average global temperatures to rise, and means more flooding because warm air can hold more water than cold air. So when all that moisture finally condenses and turns to rain, it’s more likely to fall as an intense burst.

This broad scientific principle is well established, but predicting exactly where and when extreme rainfall will occur is challenging. This is because the processes that produce rainfall are complex and change depending on the duration, location, season and the type of weather system.

The warmer the atmosphere, the more water vapour it can hold which increases the risk of heavier downpours and flash-flooding. Click To TweetDespite these challenges, the science is catching up. As mentioned above, research shows that the amount of rain that falls during extreme short-duration rain bursts in Victoria has already increased by 14%.[1]

And a cutting-edge study released in November 2022 shows that over the last two decades, extreme rapid rain bursts in the Sydney region have seen an alarming increase of at least 40% in their intensity.

With further research, it’s likely that similar trends will be observed in other areas across Australia.

The Conversation

Our research has found an alarming increase of at least 40% in the rate at which rain falls in the most intense rapid rain bursts in Sydney over the past two decades.

How does this affect you?

Unnatural climate disasters place lives, health, property, food security and critical infrastructure at risk.

Cities and towns are especially vulnerable to flash flooding because the hard surfaces (like roads and pavement) stop water being absorbed into the ground. More intense downpours mean gutters and stormwater drains – that were designed for past conditions – can quickly overflow, damaging roads, property and other infrastructure.

Flooding can also increase the risk of mosquito-borne diseases and pollute waterways and beaches.

What about La Niña?

La Niña and El Niño events are caused by variation of sea surface temperatures in the Pacific Ocean. On Australia’s east coast La Niña events result in a wet and relatively cool, spring and summer. From 2020 to 2023 we experienced three La Niña events in a row, causing extreme flooding across the state.

Scientists are still uncovering exactly how La Niña events will change as the planet continues to heat, but the latest research indicates they will become more frequent and more intense.[2]

We must prepare for many more of these damaging climate events, but of course the scale of the damage depends on how quickly we can reduce our use of coal, oil and gas.