During the 2020 lockdowns, as many Victorians took up baking or gardening to beat the Covid blues, Tuesday Browell launched her own DIY project: building a solar-powered boat.

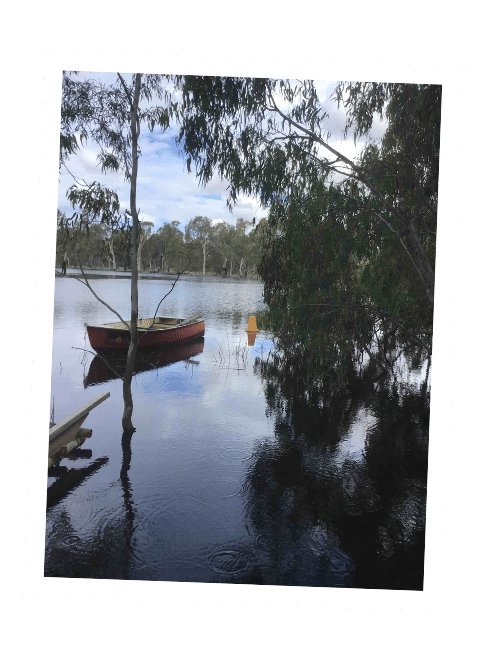

“It took three of us six months to build the Wanambe,” says Tuesday, who lives in Torrumbarry, on the Murray River. “I use the boat to walk my talk. I love the river. With an electric motor, I’m not putting fossil fuels into the water.”

Living by the Murray for 40 years, Tuesday has become a passionate defender of this ancient waterway. Encircled by Richardson’s Lagoon, her 100-acre property is a haven for native critters, including platypus, echidnas, goannas and sugar gliders.

Tuesday has seen a lot of rivers in her life – the Nile, the Suez Canal, the Laloki – but says the Murray is unique.

“It’s pretty much undisturbed native bush,” she says. “It’s a very special place.” The protected wetlands are home to more than 130 bird species, many endangered or vulnerable. The land is also rich in cultural history. An important meeting place for local Yorta Yorta clans, it’s dotted with more than 120 scar trees.

Tuesday grew up in Malta, Kuwait and Port Moresby before emigrating to Australia in the 1960s. She came to the Murray in her early 20s to help build the paddle steamer Emmy Lou. “I learnt on the job, working with skilled shipwrights. It really inspired me.” Named after a dreamtime serpent, her new boat the Wanambe is virtually silent, enabling her to witness wildlife up close.

DONATE TO POWER OUR RIVERS STORYTELLING PROGRAM

She’s seen a lot of rivers in her life – the Nile, the Suez Canal, the Laloki – but says the Murray is unique. “There’s no other river like it in the world.” It’s also the region’s lifeblood, providing fresh water, enabling food production and supporting livelihoods. “Without the river there’d be no community here. Every business and town relies on it.”

But that vital lifeline faces multiple threats. “Our summers are getting hotter and drier, and we’ve seen an exponential growth in corporate farming.” In the past five years Tuesday has seen more than 50 struggling family farms vanish, many bought out by big corporations.

The Murray is too often treated as a lucrative resource, she argues, instead of a precious ecosystem. “We’re managing the river to death. These massive water systems are made by nature, for nature. And we’re selling off the water as a commodity.”