In the last few decades, there has been a massive decline in the health of our waterways in Victoria.

As our population has grown, we’ve put more and more pressure on our rivers – taking too much water, damaging riverbanks and important habitat, letting toxic pollutants enter our waterways and more.

Human activities have taken their toll. And many impacts like climate damage are only set to intensify. This has huge implications for our water supply, the future of regional communities and the animals and wetlands that depend on a healthy river system.

We’ve listed the five biggest threats to river health in Victoria below. Click each threat or scroll down to learn more.

1. Decreased rainfall in a hotter, drier climate

Victoria’s climate is becoming hotter and drier as a result of burning polluting fossil fuels. It means there is less rainfall and less water flowing through our rivers.

2. Over-exploitation of our rivers for water

The single biggest use of water in Victoria is for irrigation. But irrigators are exploiting our rivers to the point of collapse – taking too much water away, manipulating the way our rivers are meant to flow and letting pollutants back into the water.

3. Fragmentation of important habitat

The construction of dams and weirs is stopping water flowing naturally downstream, over floodplains and into wetlands. These barriers prevent fish from migrating and starve important habitats of the water they need to survive.

4. Destruction of important habitat

When native vegetation is destroyed, it has a massive impact on the whole river system. It can result in fish and birdlife losing their habitat, erosion along riverbanks and water becoming toxic as a result of salinity.

5. Introduced plants and animals

Stock animals, weeds and introduced fish like carp are wreaking havoc on our rivers. As well as polluting the water and damaging habitat, they make it more difficult for native species to survive.

Learn about the solutions for healthy rivers

1. Decreased rainfall in a hotter, drier climate

Victoria’s climate is already becoming hotter and drier as a result of burning polluting fossil fuels.

Rainfall in Victoria has been decreasing since the 1970s, reducing the flow and amount of water in our rivers. This is particularly in winter and spring, which are the main seasons when rainfall replenishes our rivers, reservoirs and groundwater.

This situation is exacerbated by the way water is shared between users and the environment. In most river systems, there is a cap on the amount of water that can be diverted for use – and any water that is left over after that (‘above cap’ water) is for the environment.

When inflows are reduced by drought or climate change, the environment’s share of water is impacted the most. Users may have to cope with less water through restrictions or reduced allocations, but the environment may have to go without its share altogether.

If we continue this way under a hotter, drier climate that’s predicted, our rivers simply won’t have enough water to survive. We need guaranteed water to get our rivers flowing – not just to keep them alive, but to let rivers be rivers.

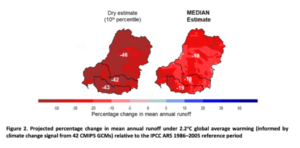

Climate damage is also one of the biggest threats facing the Murray-Darling Basin. But when it came to developing the national plan in 2012, the Murray-Darling Basin Authority completely glossed over its impacts (and ignored the modelling that they had commissioned!) after lobbying from powerful irrigators and politicians.

Australia’s most important river system is already feeling the impacts of less rainfall and scientists predict that water flowing through rivers and streams may decrease by up to 50 percent. During extended droughts, flows might decrease up to 70 percent.

Source: Plausible Hydroclimate Futures for the Murray-Darling Basin A report for the Murray–Darling Basin Authority’ by CSIRO, Dec 2020

2. Over-exploitation of our rivers for water

Across Victoria, we have historically relied on rivers, wetlands, lakes and underground water systems to supply the water we use. But as our demands have grown and a hotter, drier climate has reduced the amount of rainfall our rivers have been depleted.

While we use water for many things in our homes, schools, hospitals and towns, the single biggest use is for irrigation of almond trees, citrus orchards, grapevines and pasture for dairy farms.

The big irrigation areas are in northern Victoria, along rivers like the Murray and the Goulburn. Large dams like Lake Eildon and the Dartmouth Dam have been built to hold thousands of gigalitres of water to supply the industry. But there are problems with the way our rivers are being exploited for their water:

Taking too much water

Most rivers can cope with some of their water being extracted without suffering long-term impacts. But unfortunately, in Victoria and right across the Murray-Darling Basin, irrigators are taking too much water away – even in dry years. It has pushed many rivers to the brink of collapse.

For example, at times the Goulburn has had up to 80% of its water taken for irrigation and up to 90% of the flows in the Moorabool have been extracted urban and agricultural use. There have been times when some rivers like the Avoca or Wimmera have stopped flowing altogether, while others like the Merri or Powlett have had such low flows that their estuaries close to the sea.

Manipulating the natural flow of rivers

Rivers naturally flow differently during different seasons and years. Generally in Victoria, river flows are high in winter when it rains and low during the hot, dry summer.

But irrigators have completely ignored this pattern. They want to take the most water during summer when rivers are naturally at their lowest.

To manipulate the river system in their favour, they’ve lobbied governments for huge new dams and water storages to capture water. In the process, they’ve destroyed the natural ebbs and flows of the river that support fish, frogs, turtles, wetlands and all river life.

In winter, water is diverted into dams to benefit irrigators. This means river flows are far lower than they should be, and prevents fish and birdlife from being able to breed. Capturing water in dams can also stop water from reaching the floodplains and wetlands that rely on seasonal flows, and is a huge threat to the survival of flood-dependant vegetation like the River Red Gum.

In summer, irrigators use the river like a pipe to force huge amounts of water downstream – cutting into riverbanks, washing away vegetation and destroying important fish habitat.

Polluting river water

Chemicals such as fertilisers, herbicides and fungicides are commonly used in agriculture. When extra nutrients from these (like nitrogen and phosphorus) get washed back into our rivers, it can have disastrous consequences.

Raised levels of nutrients encourage algal growth – and if flows are low and the weather is warm, algal blooms can quickly form. These block light and smother other organisms, and in the case of blue-green algae can release toxins that are harmful to stock and humans. Their rapid decomposition can also reduce the oxygen content of the water which means that fish find it difficult to breathe and can die.

Algae in the Moorabool River in 2017

Bushfires can also cause major pollution and have a big impact on water quality, especially if it rains following the fire. Fire retardants and ash can be washed into rivers, and significant erosion often follows. Read more about how bushfire ash can damage our waterways here >>

3. Fragmentation of important habitat

A healthy river system needs to be connected, so water can flow downstream, over floodplains and into wetlands. This connectivity is what allows fish, turtles and platypus to migrate. It keeps the water clean by providing a corridor for nutrients and sediment to move around. And it brings wetlands to life, sustaining giant river red gums and providing the habitat for waterbirds to breed.

This can be impacted by the construction of barriers, including:

Instream barriers – dams and weirs that have been constructed across the course of the river

Most Victorian rivers are dammed and have many barriers of varying sizes. The only major free flowing rivers in Victoria are in East Gippsland and the Otways, as well as the Ovens River in the Murray-Darling Basin.

These barriers present a major obstacle to fish mobility and migration, as the only way for fish to get around them is with the construction of a suitable fish ladder.

Farm dams – small, private dams that capture water before it gets into the river system

If lots of farm dams are constructed in one catchment, it can have a big impact on the health of the river system. In dry years, it can mean most of the available water is captured in these dams instead of flowing into the rivers and wetlands that depend on it.

4. Habitat destruction

Victoria is the most intensely cleared state in Australia – with over 50% of native vegetation destroyed during the two centuries since European invasion.

The impact of habitat destruction on our native plants and animals is huge, often affecting many different species at once. These three types of damage have particular impact on rivers:

Land clearing

A lot of native vegetation along riverbanks has been removed, and many wetlands have been bulldozed to make way for agriculture or urban development. As well as destroying important habitat, this also increases riverbank erosion and salinity.

Some river channels have been cleared to remove logs and branches (snags). But this woody habitat is vital for aquatic life. Fallen trees and snags give fish like the Murray cod a place to lay eggs, hide from predators and rest from fast flowing water.

Erosion

Erosion has clear and direct impacts on the health of riverbanks, but can also cause damage by washing extra material into rivers.

An example of this is in the Upper Murray, Kiewa and Ovens Rivers . Sediment dug up from gold mining in the late 1800s has been deposited all along the riverbed, clogging up deep holes that normally act as drought refuges and are favoured by native fish. The ‘sand slug’ has moved downstream to the Barmah Narrows, where experts estimate more than three million tonnes of sand have settled along 24km of the riverbed!

Other rivers like the Glenelg are also facing challenges from massive sand slugs.

Salinity

Much of the groundwater in Victoria is naturally saline (containing salt), but the deep roots of native vegetation have historically helped hold this well below the surface.

When native vegetation is destroyed, these root connections are also severed. This causes the salty water table to rise, which can bring with it dryland salinity. Given that much of Victoria’s groundwater drains into our river systems, salinity can have extreme consequences.

Groundwater intrusion into the Wimmera River during the Millenium Drought raised its salinity levels to more than double that of seawater. The result? Dead trees and unusable water that was toxic to stock and wildlife.

During the Millennium drought, the Wimmera River stopped flowing. Lack of water flow coupled with historic land clearing caused salty groundwater to came to the surface and penetrate the river bed.

Salinity can also be worsened when irrigators take more water than they need. This is because excess water drains down into groundwater – raising the water table, with the same impact as clearing native vegetation.

5. Introduced plants and animals

Pest plants and animals are just as much as a problem in water as they are on land. Below are three examples:

Stock access

In Victoria, over 30,000 km of land bordering a river belongs to the state. This land, known as a Crown frontage, varies in width from a few metres up to kilometres, and was reserved in the 19th century as a public resource. While some of this land is in public reserves, over half is managed by the adjacent land holder under a licence.

Most of the licences are used for stock grazing, which allows animals like cows to wander in and around riverbeds to drink and cool off. But this causes devastating damage to our rivers.

Stock animals remove much of the understorey vegetation, destroy habitat for native wildlife, cause bank erosion and pollute the water with faeces. Millions of dollars have been spent fencing off streams, yet grazing licences are regularly renewed without any changes.

Environment Victoria successfully campaigned for an extra $30 million to protect river health and get livestock off riverbanks in the 2015-2016 Victorian state budget. Read more here >>

Weeds

Willows were planted on riverbanks throughout Victoria during the 20th century to help with bank stabilisation. But it’s had the opposite effect!

Willows have been responsible for increased flooding, degraded water quality and damage of aquatic habitat. They are now classified as a Weed of National Significance and millions of dollars are spent every year on their removal.

Other problematic aquatic weeds include cabomba, parrot feathers and Azolla which all affect water quality.

Noxious fish

Sadly, there are now far more introduced fish in Victorian waterways than native fish.

Carp were introduced in the 1880s and now account for up to 90% of fish biomass across the Murray-Darling Basin. Described as ‘the freshwater rabbit’, they can out-compete native fish and their bottom feeding habits stir up sediment which affect water quality and bank stability.

Trout have been common for a lot longer in cooler waters and are still frequently stocked for recreational fishing. But their predatory habits pose a massive threat to small native fish such as endangered mountain galaxias. Trout exclusion zones have had to be established in some mountain streams to protect native fish.

When irrigators manipulate the natural flow of a river, it can also advantage introduced species over native fish. Carp often spawn downstream of dams that release water at temperatures too cold for native species. They are also much more resilient in droughts.

Recent efforts by the Victorian government stand to make this imbalance worse. Rather than flooding wetlands naturally, the government has been increasingly focused on installing infrastructure like pumps and regulators to artificially deliver water to floodplains. These projects will provide the shallow, warm, slow-flowing waters where carp thrive.