1. Why is a plan to manage our rivers so important?

As population growth drives ever increasing demand for water, we are also facing the consequences of a damaged climate, where less and less water is flowing into our rivers.

These trends are intensifying, and we need to think carefully about how we use water, where we get it from and the impact that has on our rivers, local communities and environment.

Click to read more about the impacts of climate change and population growth

Click to read more about the impacts of climate change and population growth

In southern Victoria, we have historically relied on rivers to supply the water we need in our homes and our towns. Rivers have been a source of life and joy.

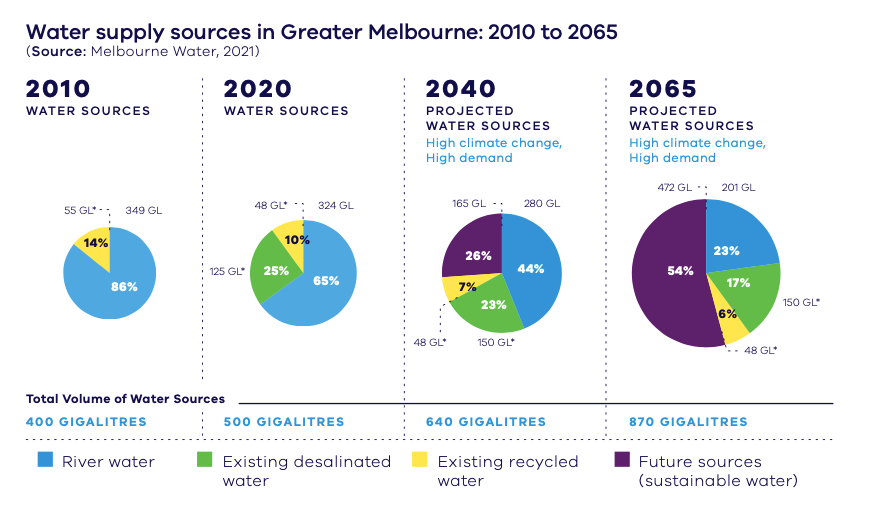

But as our demands have grown and a hotter, drier climate has reduced the water available, we have had to turn to other sources. In 2020, 25% of our water came from the desalination plant at Wonthaggi and 10% came from recycled water.

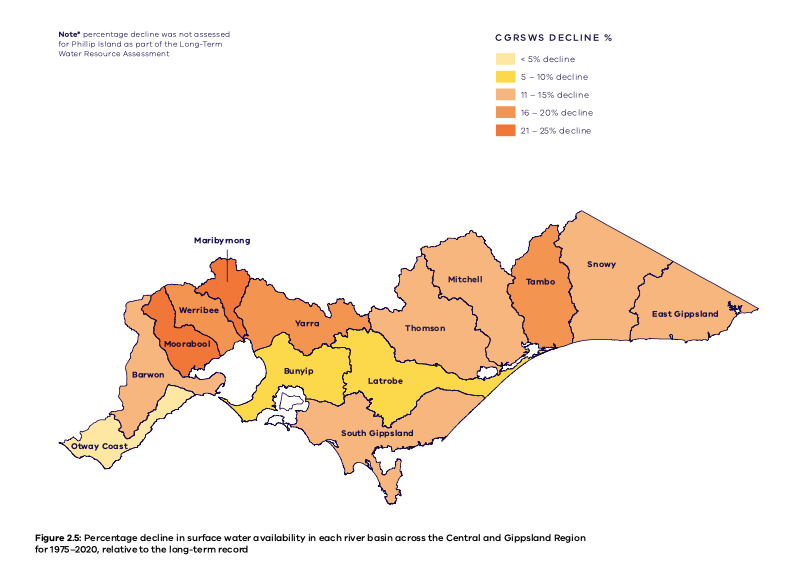

Compared to the historic average, the amount of water flowing into our rivers, lakes and wetlands has declined by as much as 21% over the past 10-15 years. Under a medium climate change scenario, these declines may continue by a further 8– 22% by 2065. Under a high scenario, by a further 40%.

Source: Victorian government's Central and Gippsland Region Sustainable Water Strategy Discussion Draft

This is a confronting preview – but it is one we can respond to.

We need to think about how we live with our landscape and how we have changed our landscape. Now that we face the joint challenges of climate damage and population growth, we need to think about how we can make the landscape more resilient, and our use of water fairer and less extractive – in our lifetime.

To correct our course, we need a plan. For the Victorian government, the goals and parameters of this plan are set through the Sustainable Water Strategy, which we now have a chance to influence.

2. What is the Sustainable Water Strategy?

The Sustainable Water Strategy (SWS) deals with the next 50 years of water management for southern Victoria. This is a region stretching from the Great Divide to the coast, from East Gippsland to the Otways.

Click to read more about how the plan aims to address decreasing water supply and increasing demand

Click to read more about how the plan aims to address decreasing water supply and increasing demand

The Strategy considers how the amount of water flowing into our rivers has declined, how demand will grow and how competing uses must be balanced with the essential needs of the landscape.

We already have a preview of declining water supplies – somewhere between 8 and 40% over the next 45 years. But as Victoria’s population grows, demand might be 1.7 times higher over the same time period. This is clearly a bad combination.

What it translates to is that by 2065, over half of the water southern Victoria needs does not currently exist.

Source: Victorian government's Central and Gippsland Region Sustainable Water Strategy Discussion Draft

The Strategy deals with broad questions. How do we save water by being more efficient? How do we grow water supplies? How do we manage water equitably between all uses?

Since a healthy society ultimately depends on a healthy environment, it’s worth focusing on one: what does this mean for our rivers?

3. How does the plan fail our rivers?

In this deal, water for rivers is far from guaranteed. Instead of a plan to increase river flows, waterways are dependent on the leftovers after industries and cities have had their fill.

The best the government’s draft strategy can say is this: if other sources come online and if other industries have had their fill and if there is more water available … it could maybe flow through rivers.

Click to read more about why water for rivers isn’t guaranteed in the plan

Click to read more about why water for rivers isn’t guaranteed in the plan

This Sustainable Water Strategy is founded on one key recognition: rivers cannot give up any more water to meet future demand.

What follows then is a strategy of substitution. Essentially, if we manage to grow water supplies with greater use of stormwater, desalination and fit-for-purpose recycled water, then those sources can substitute water taken from rivers (known as extraction). Water that used to be taken from rivers would then be free to flow.

This is a reasonable approach for addressing growth in consumptive uses like in our homes and cities. Partially because it looks like the skeleton of a plan – ‘we need more water, so let’s grow the pool of water’. Fair enough.

But in this deal, water for rivers is far from guaranteed. Instead of a plan to increase river flows, waterways are dependent on the leftovers after industries and cities have had their fill.

What’s worse is that any water saved for rivers is already playing catch-up with the impacts of climate change (the 21% decline we’re already facing).

So the best the government’s draft strategy can say is this: if other sources come online and if other industries have had their fill and if there is more water available … it could maybe flow through rivers.

That’s not good enough. Rivers need a better answer to the question of their long-term survival than ‘maybe’.

But how much water are we talking about? The Strategy sets out potential maximums, ‘up to X megalitres per year’ figures for different rivers. These ‘maybe’ targets are based on avoiding the loss of critical species and cease-to-flow-events. But this should be the bare minimum.

Instead of this ‘maybe’ approach, targets should be guaranteed – and they should be set to do more than keep rivers on life support. We need enough water to let rivers be rivers, and that means connectivity.

4. Why is connectivity so important for healthy rivers?

One foundation of a thriving river is connectivity. It is connected from upstream to downstream; from the channel to the floodplain forests over the banks; and between surface water and groundwater.

When we extract too much water and don’t sustain these processes, it threatens the entire river system and landscape. A river without connectivity means a river without fish, platypus, waterbirds, shade, quality water and healthy soil.

Click to read more about the ecological importance of a connected river system

Click to read more about the ecological importance of a connected river system

This supports a healthy ecosystem in the following ways:

-

- When a river is connected from upstream to downstream, it means fish, turtles and platypus can move freely. It also means that salt, nutrients and sediments can move. When they cannot flow through, water that gets too salty can kill aquatic life. Sediment can block the light that plants and phytoplankton need, favouring algae instead. This can degrade water quality and encourage toxic algal blooms.

-

- When a river is connected to its floodplain, it brings wetlands to life. It sustains riverside forests and allows waterbirds to breed. Water from the river deposits nutrient-rich silt and sediment that makes the floodplain fertile. And when it returns to the river, it carries leaves and wood with carbon that supports the entire food web. Without floodplain connectivity, a river is little more than an empty irrigation channel.

-

- When a river is connected between surface water and groundwater, it can recharge groundwater supplies. Groundwater can contribute flows into wetlands or back to the river at certain places or times of year, cooling the water and bringing dissolved minerals with it.

5. What does a better plan for our rivers look like?

In summary, the draft Sustainable Water Strategy presents a big ‘maybe’. If we can grow our water supplies to sustain nearly double today’s demand, then maybe there will be some water leftover to flow through rivers.

What we need instead is a plan that works backwards from waterway health. This is the approach that was put forward (but only half-heartedly implemented) in the Murray-Darling Basin Plan.

Click to read more about the steps the Victorian government could take to let our rivers be rivers

Click to read more about the steps the Victorian government could take to let our rivers be rivers

A responsible plan would begin by using the best science to identify an ‘Environmentally Sustainable Level of Take’ – a baseline for how much water needs to be kept in rivers for them to thrive over the long-haul. Not just river survival but ensuring the foundational conditions of a healthy waterway.

This is the opposite of our current system. Today, 95% of water for the environment is ‘leftover water’ – and under a hotter, drier climate, there is less and less of this water available.

Next, we need to take actions that reduce extraction, so enough water is kept in our rivers.

This requires a sensible and courageous government to recognise that the current level of privatisation of our water cannot go on in a drier climate. Some water will need to be bought back from license-holders to confront historic over-extraction.

Right now, this isn’t even on the table. But this alone isn’t enough. For example, to ensure the health of the Barwon River system, at least 44 billion litres of additional water needs to flow through the river. But this is more than the amount of water that is actually extracted (42 billion litres).

Clearly, we can’t stop all consumption, so we need a credible plan to fill the gap. As with consumptive demands, rivers may need water flows supplemented from fit-for-purpose manufactured sources. But these options are expensive. It is nonsensical to consider manufactured or treated water for rivers before we consider simply taking less.

Finally, this water needs to be protected so rivers always have a fair share of their own water.

This demands reform of the ‘Environmental Water Reserve’ in Victoria’s Water Act. While this is a much bigger scope than the Sustainable Water Strategy alone – it won’t happen without laying out ambitious priorities in the Sustainable Water Strategy now.

Skip to our three key solutions for a plan that lets rivers be rivers >>

6. How to get involved

The Victorian government will finalise their plan in the middle of this year, which will set our rivers up for the next 50 years of water management.

The survival of our rivers and the incredible diversity of life they support rivers is something that affects us all. That’s why we’ve been working with community groups across the state to stand up for our local rivers and show Minister Neville just how many Victorians want to see them protected.

Together, we’ve created an Open Letter, calling on Water Minister Lisa Neville to prioritise healthy rivers in the Sustainable Water Strategy. Add your name to the Open Letter >>

By standing together, we can influence a better plan and make sure our rivers have the water they need to survive and thrive – long into the future.