The vision

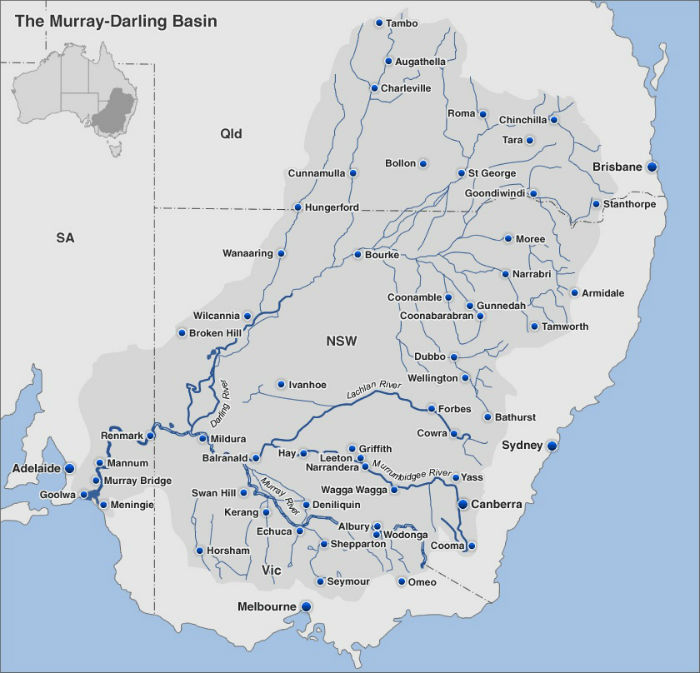

The Murray Darling Basin Plan was supposed to fix this. Back in 2007, Prime Minister John Howard’s vision was for “radical and permanent change” to the way our biggest river system was managed.

Howard said the Basin Plan would address over-allocation of water “once and for all”. It would reduce how much water could be taken from the river, leaving enough for the wetlands, forests, birds, fish and frogs to survive.

Bastardising the Basin Plan

But having a plan is one thing, and following through on it is another. Right from the start, a handful of powerful corporate interests and their cashed-up lobbyists have lobbied governments to undermine the Plan and rig the rules in their favour.

With every political sell-out and backroom deal, the vision behind the Basin Plan has been bastardised:

In the news: The Basin Plan has been compromised at every turn.

- The total amount of water to be returned to rivers is far below what the science recommends. [1]

- Recovering that water for the environment has been constantly delayed. [2]

- The cheapest and most effective method of recovering water for the environment – buying it back – has been ruled out in favour of dubious ‘efficiency’ projects. [3]

- Governments have turned a blind eye to blatant water theft. [4]

- Some landowners have built earthworks to capture floodwaters in huge private dams, instead of letting it flow naturally down the river. NSW is now attempting to make this unfair practise legal. [5]

- Private property is blocking natural floods from reaching the wetlands that need them. Only 21 percent of water for the environment floods over the bank to keep the floodplain healthy. [6]

The list goes on, each political deal undermining the whole point – to reduce how much water is taken from the river.

After years of this, we’re in a situation that benefits a chosen few. Water is going to the people with the most money or the best connections, leaving the community and environment to suffer.